When veterans become cops, some bring war home

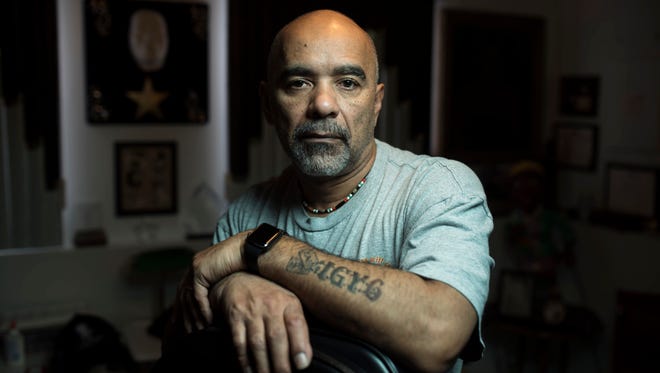

William Thomas, a retired Newark police sergeant, left his home in a body bag.

To his dismay, he was still very much alive. A team of police officers and medical technicians had strapped his limbs together, stuffing his body into a mesh sack to restrain him after he tried to fight them off.

Six hours earlier, Thomas, a decorated narcotics investigator and a veteran of the New Jersey Air National Guard, tortured by post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a result of his service in Iraq, had downed a fistful of prescription sleeping pills with an entire bottle of Bermuda rum. He collapsed onto his stepson’s bed, calmly waiting to die. This was the second time since returning from war and rejoining the police force that he had tried to take his own life.

The debate over the militarization of America’s police has focused on the accumulation of war-grade vehicles and artillery and the spread of paramilitary SWAT teams. What has gone largely unstudied, however, is the impact of military veterans migrating into law enforcement. Even as departments around the country have sought a cultural transformation from “warriors” to “guardians,” one in five police officers are literally warriors, returned from Afghanistan, Iraq or other assignments.

The majority of veterans return home and reintegrate with few problems, and most police leaders value having them on the force. They bring with them skills and discipline that police forces regard as assets. But an investigation by the USA TODAY Network and The Marshall Project indicates that the prevalence of military veterans also complicates relations between police and the communities they are meant to serve.

To the obvious question — are veterans quicker to resort to force in policing situations? — there is no conclusive answer. Reporters obtained data from two major-city law enforcement agencies and considerable anecdotal evidence suggesting veterans are more likely to get physical, and some police executives agree.

But any large-scale comparison of the use of force by veterans and non-veterans is hampered by a chronic lack of reliable, official record-keeping on police violence.

Some other conclusions about military veterans in the police force emerged more clearly:

- Veterans who work as police are more vulnerable to self-destructive behavior — alcohol abuse, drug use and, like Thomas, attempted suicide.

- Hiring preferences for former service members that tend to benefit whites disproportionately make it harder to build police forces that reflect and understand diverse communities, some police leaders say.

- Most law enforcement agencies, because of factors including a culture of machismo and a number of legal restraints, do little or no mental health screening for officers who have returned from military deployment, and they provide little in the way of treatment.

When Thomas returned to Newark, the police department offered no services for returning veterans, and he says he probably wouldn’t have applied for help anyway, fearing a stigma. “I just went back to work like nothing happened,” he says.

He lasted eight days in police uniform before his first suicide attempt. Tormented by memories of an explosion at the Baghdad airport that killed a favorite K-9 patrol dog, unnerved by crowds, spooked by loud noises and argumentative with superiors, “I tried to eat my gun,” he says.

His wife drove him to a nearby veterans hospital, where Thomas was diagnosed with severe PTSD. Thomas, now 57, is an advocate in the non-profit military and veterans support group Wounded Warrior Project.

The vet-to-cop pipeline

Policing has long been a favored career choice for men and women who have enlisted in the armed forces.

Today just 6% of the population at large has served in the military, but 19% of police officers are veterans, according to an analysis of U.S. Census data by Gregory B. Lewis and Rahul Pathak of Georgia State University for The Marshall Project. It is the third most common occupation for veterans behind truck driving and management.

The attraction is, in part, the result of a web of state and federal laws — some dating back to the late 19th century — that require law enforcement agencies to choose veterans over candidates with no military backgrounds.

In states with the most stringent hiring preferences, such as New Jersey and Massachusetts, a police applicant who was honorably discharged from the military leaps over those who don’t have those credentials. Disabled veterans outflank military veterans with no documented health concerns. Thomas, the PTSD-afflicted Newark cop, held a secure place on the sergeant's promotions list because of his time with the New Jersey Air National Guard.

The Obama administration helped expand the preference: In 2012, the Department of Justice provided tens of millions of dollars to fund scores of veteran-only positions in police departments nationwide.

Official data on police officers who are veterans are scarce. Nearly all of the 33 police departments contacted by The Marshall Project declined to provide a list of officers who had served in the military, citing laws protecting personnel records or saying the information was not stored in any central place. The Justice Department office that dispenses grants to study policing said it had no interest in funding research into how military experience might influence police behavior.

But even those who advocate hiring combat veterans as police officers have raised alarms. The Justice Department and the International Association of Chiefs of Police put out a 2009 guide for police departments to help with their recruitment of military veterans. The guide warned, “Sustained operations under combat circumstances may cause returning officers to mistakenly blur the lines between military combat situations and civilian crime situations, resulting in inappropriate decisions and actions — particularly in the use of less lethal or lethal force.”

“A PTSD moment”

In 2012, Iraq War veteran and Albuquerque police officer Martin Smith responded to a call about a suspicious black SUV. Seconds later, he shot and killed the unarmed driver through the driver side window. In court papers, lawyers for the dead man’s family said Smith “later told his co-workers that he ‘blacked out’ and had a ‘PTSD moment’” during the shooting.

Smith had returned from deployment at a time when law enforcement across the country “was really trying to figure out how best to deal with the number of folks who were being activated,” then–police chief Ray Schultz said in depositions. According to court papers, Smith re-joined the force with a 100% disability rating, suffering from flashbacks, blackouts, and waking-nightmares; nevertheless, the department assigned him to patrol a high-crime area of town known as “the War Zone.”

The Albuquerque force has been cited by the Justice Department for a high rate of unconstitutional police-involved shootings. According to documents provided to The Marshall Project by Albuquerque police, of the 35 fatal shootings by police between January 2010 and April 2014, 11, or 31 percent, were by military veterans. Neither the Albuquerque Police Department nor the city attorney responded to questions about the shooting.

In two other cities that agreed to provide data to The Marshall Project — Boston and Miami — internal police records indicate that officers with military experience generate more civilian complaints of excessive force. Without knowing such details as age, duration of military service and the location of the incidents, it is impossible to rule out other factors, but in both cities the difference is noteworthy:

- In Boston, for every 100 cops with some military service, there were more than 28 complaints of excessive use of force from 2010 through 2015. For every 100 cops with no military service, there were fewer than 17 complaints. Spokesman Michael P. McCarthy said the department would look into the disparity.

- In Miami, based on data from 2013 through 2015, for every 100 veterans on the force, 14 complaints were filed; for every 100 officers without military service, 11 complaints were filed.

The Marshall Project also obtained data for the Massachusetts State Police, which showed no significant difference in complaints against veterans and non-veterans for excessive force.

The International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), the largest organization of policing executives,published a survey of 50 police chiefs in 2009 about their experiences integrating returning soldiers. Fourteen percent reported more citizen complaints against veteran officers, 28% reported psychological problems, and 10% saw excessive violence.

More coverage:

Vet hiring preference hinders police diversity

Cop2Cop offers peer support to New Jersey's finest willing to come out from behind the shield

Focus on psych tests as more vets apply to be police

The Other ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’

When police officers return to work after a military deployment, federal law — the Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act — prohibits their departments from requiring blanket mental health evaluations. Because of the Americans With Disabilities Act, police departments can’t reject a job candidate for simply having a PTSD diagnosis.

The only time most of America’s law enforcement officers are required to sit for a mental health analysis is during the initial hiring process, and the rigor of the screening varies widely. Fewer than half of the nation’s smallest police departments do pre-employment psychological testing at all, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Many offer “screenings” in name only, says Stephen Curran, a Maryland police psychologist who has researched the transition from the military to policing — in some cases simply a computerized test with no face-to-face interview.

Where there is systematic testing of would-be police, military veterans are more likely to show signs of trauma.

Matthew Guller,

a police psychologist, is managing partner of a New Jersey firm, The Institute for Forensic Psychology,

that works with about 470 law enforcement agencies across the Northeast, screening for impairment.

Of nearly 4,000 police applicants evaluated by Guller’s firm from 2014 through October of 2016, those with military experience were failed at a higher rate than applicants who had no military history — 8.5% compared with 4.8%.

The higher rates of trauma are exacerbated by the fact that service members with PTSD often aren’t diagnosed and keep quiet about their suffering. Although up to 20% of those deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan have PTSD, only half get treated, according to a 2012 National Academy of Sciences study. Veterans are 21% more likely to kill themselves than adults who never enlisted, according to a report in August by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Officers with a history of mental health problems — even those who have been treated and are now healthy — can pose a twofold problem for departments who hire them. First, their history can become a liability if the department is sued. Second, it can be used to attack their credibility on the stand if they’re called to testify.

Advocates say the safety net for struggling officers at most police departments is minimal to non-existent. Even departments sensitive to mental health are in a difficult position: Top brass needs to be able to take unstable police officers off the street lest they hurt someone or themselves on the job. Yet officers must feel they can ask for help confidentially, without jeopardizing their careers, or “you're never going to get cops to come forward” for treatment, says Brian Fleming,

a retired Boston police sergeant who ran the department’s peer support unit from 2010 to 2014.

The lack of official attention in many cities has spurred police unions and individual officers to construct their own safety nets, programs where officers can open up about pain they would never show at a station house.

“I’ve never been at a roll call and someone says: ‘Know what, Sarge? I feel sorta sad today,’” says Andy Callaghan,

a Philadelphia police narcotics sergeant who spends his spare time at the Livengrin Foundation for Addiction Recovery

outside Philadelphia, counseling police and combat veterans with mental health struggles. “Early intervention is the key. Waiting for someone to self-destruct is what we do, and it's terrible.”

Additional reporting by Tom Meagher, The Marshall Project

This article was reported in partnership with The Marshall Project, a non-profit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletter, or follow The Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.